Dear Reader,

‘My exhaustion today is like a glaze.’1 I am reading aloud and when I reach this sentence I laugh. I am reading to my son who will not nap. We are sitting on the floor in his room and he is pulling book after book into his lap, palming the pages. His afternoon nap is a time I cherish because it is around this time of day my pelvic floor simmers brightly—scar tissue, contraction. No, the better word is ‘undulation’.

What I’m saying: it is a rare day I reach this hour without needing to lie down. Before he was born I slept on my left side, facing the window and its swatch of afternoon. Now that he is here I sleep with him on my body, his head fitted under my chin or slipping off my shoulder.

A glaze.

On the windowsill, a bookend. A block that is a head and the back of it flattened so it will sit flush against the wall. But, glancing up now, what I see is a faceless woman and her facelessness makes perfect sense to me.

My son is thirteen months old.

When he was four months old I sat with a psychiatrist who said ‘I’m hesitant to diagnose you.’

Then and now: I am often incandescent. Turgid, ripe with joy.

But, still—a glaze.

My baby has been teething for what seems like months but now he is himself again, interested in sound and gesture and almost always laughing. People tell me he is flirtatious, often in the moments after light has played, just so, across his eyes.

A few weeks ago, someone asked me ‘What would you tell a new mother?’

As if I am not myself freshly born, trailing membrane around the house. But: there are some things I can imagine saying to a mother a few months or a year behind me.

Lock yourself away until you’ve made up your own mind about breastfeeding.

No one will help you as much as they said they would. They did not know what they were offering at the time.

This dipping in, these small, relatively unpredictable stretches of company and support. It does nothing to smooth out the hard angles of our days, the weird loneliness of our wide long nights.

One afternoon, one evening of baby-care. It doesn’t scratch the sides. It doesn’t touch the surface.2

*

I look at my baby, still undesirous of sleep, and say ‘You could not have been more wanted. Your face transforms my day.’

I think, You owe me nothing. Never feel you owe me anything but the basic kindness I hope you’ll show any feeling creature. The rest is a series of glittering gifts I won’t take for granted.

This, and other things, I’m not yet able to say out loud without an intensity that might frighten him.

love for the child

is animal

not love

but hunger3

*

No—I’d say Only when he turned nine months did I begin to feel like his mother and not a woman who’d had her stomach cut open, been handed a baby and sent—smiling, limping—back into the world.

*

I would die without him.

I will die if I do not sleep.

Ambivalence is not the quick shift from one conflicting feeling to another. It is two cars driving down the highway. Sometimes it seems one will overtake the other, but it never happens. They carry on driving side by side.

These simultaneous feelings lately.4

*

No—I’d say Get feral, fast. Don’t let anyone touch your child. No one is permitted to lift your baby off your lap or chest.

No. I’d say I too have sat in a room with my impossible dream of a child come true and offered the devil a pint of my blood, to not feel so alone.

*

When my baby is four months old I start sitting down with my laptop at 5am. I am working on my third novel and the devil is still with me. He is small, coal-black. He tells me ‘No one cares if you write another book.’ ‘Yes’, I say, ‘I know.’ While I type my sore breasts refill with milk. Beside my laptop, the monitor where I can see my husband and my son sleeping—the coarse monochrome makes the duvet ripple silver. ‘You are not a bestseller. You have no great gift. Yours is not a rare voice.’ ‘Yes,’ I say, ‘I know.’

Two screens next to one another.

On one, the hot blood of my body rendered in word upon word.

On the other, two lush segments of my heart turn toward one another. Begin to stir.

*

When my baby is eleven months old I say ‘I cannot in fact finish this book.’ I started writing it before I was pregnant. It has multiple timelines and narrative voices and a mother-child relationship at its core. Almost five years of drafting, editing. It is sticky and overwrought. My father calls me on my way to pick up my son from his three and a half hours at crèche and I am crying.

That morning I told my husband something along the lines of ‘Writing it is hurting me too much.’

Days later, I read Olga Ravn’s short story “Maintenance, Hvidovre” and her interview in The New Yorker. They are about childbirth, about the fate of the life of the mind after one has a child.

I wanted to have no fear, I wanted desperately to name all these frightening, weird things, I wanted to deepen my relationship with art and writing, and this material took me deeper than anything.

Her words pass a breath into me and it’s a breath of fire, a breath I pass into the mouth of a character who’s been giving me trouble. This woman I have made, she looks up at me from the page and tells me ‘I did not want my vagina to be torn.’

It is enough. Nine words—simple, straight. But, something in their straightness and their rhythm. I tell my husband ‘No, fuck it, I will finish it.’ I tell my agent. I have three weeks. My mum and my sister collect my baby from crèche for ten straight working days. I take out eighty pages and rewrite one hundred. The meat of my palm is a crunching ball of sinew. When I lie down at night I dream of my longhand pages, turning over.

*

Of her hybrid-genre book Incubation: a space for monsters, Bhanu Kapil says

It is deleted by a friend visiting me one day, it doesn’t return, I have to write it again in two weeks while my son is in Montessori…5

I know, now, to always have at hand a book by a writer who is touching in some way upon her motherhood. To remind me, that it can be done. To be a writer and a mother, both.

have I forgotten writing

as the place

I can redeem myself6

Crack this spine, take a look.

Alone, but not so alone.

*

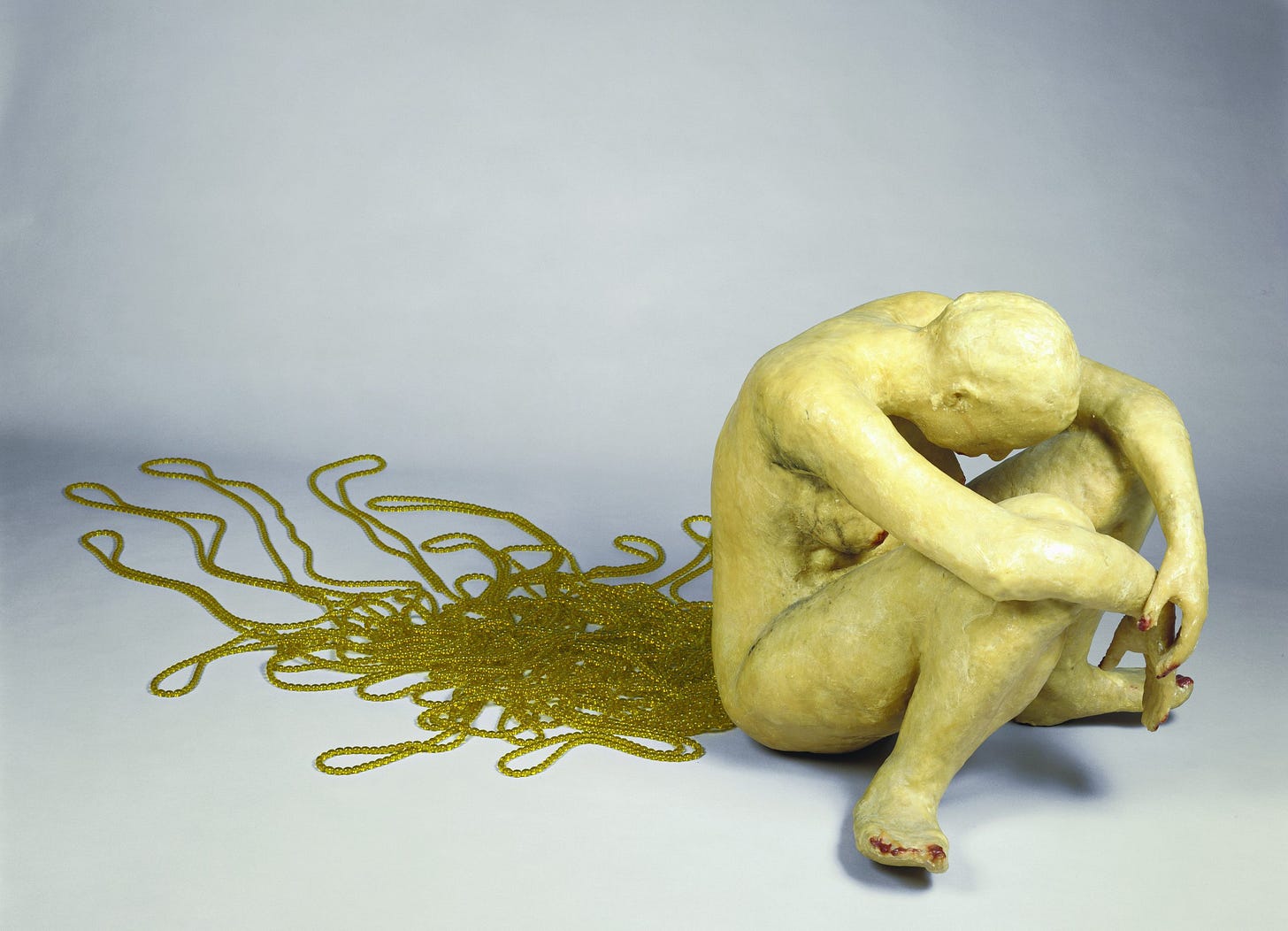

No. I would say I do not know what I am doing. But oh, my god. Look at you. You are pure light, warm and illumed. Nobody has ever done this thing as magnificently as you. I’ve seen where you are bleeding, and you are exquisite. Just now, when you put your hand on your baby, and they turned to you—it was a frisson, a miracle-burst. I swear to you with all the breath in my body that I have never seen anything like it.

*

WRITING PROMPT

Set your alarm for 3am and, by the very dimmest light and without making any noise, write 500 words. You can stop only to adjust your breasts and only if they are sore. If there is a devil beside you, disembowel him. Use your pen as a quick sharp blade.

Kate Zambreno, The Light Room, Riverhead Books 2023, 19

Kate Briggs, The Long Form, Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2023, 111

Olga Ravn, translated by Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell, My Work, Lolli Editions, 2023, 38

Zambreno, 31

Between The Covers with David Naimon, interview with Bhanu Kapil: https://tinhouse.com/transcript/between-the-covers-bhanu-kapil-interview/

Ravn, 38

Love this so much.