Welcome (by the skin of my teeth on the last day of the month) to the first instalment of A Penny Spinning! It’s wonderful to have you, you gorgeous reader of the niche and obscure where the visual and literary arts are concerned.

The piece I’m sharing today is one I started writing in 2016 after seeing The Passion According to Carol Rama at the Irish Museum of Modern Art. I went to the opening, attended a critical lecture by Griselda Pollock and a curators’ talk by Paul B. Preciado and Teresa Grandas (Preciado’s Testo Junkie would play a vital role in my later research).

Over the years, I’ve read versions of this piece to visual art audiences, and while I often detect pockets of possible expansion in the prose, whenever I try to add a line of historical context (the rise of fascism in Italy) or an extra biographical note (her father’s suicide) it feels immediately heavy-handed and overwrought.

I felt compelled to share this piece in particular as a first instalment rather than some of the other pieces I’ve let percolate over the years, because I still feel Rama is nowhere near the level of acclaim she’s owed, and that much of the acclaim she’s received comes with an ugly footnote attached. Namely, details that promote a kind of eccentricity and madwoman mythology, as if there were a reason other than its inherent biases that caused art history to neglect her for so long.

I’ve made the entirety of this piece and its supplementary info—a writing prompt I wrote specifically for “Masturbazione” as well as further reading and listening relating to Rama—available to all subscribers, as seems to be the way with the first post on these things.

I hope you enjoy!

*

PHANTOM IN RED

ON CAROL RAMA’S “MASTURBAZIONE” (1944)

Carol Rama lived in an apartment on a river in Turin. She kept black curtains pulled across the tall windows because she preferred to paint in the dark. The unlit rooms were piled high with her canvases. Deemed pornographic and banned as a result, they filled the apartment—thickened and bolstered Rama’s domestic shadows.

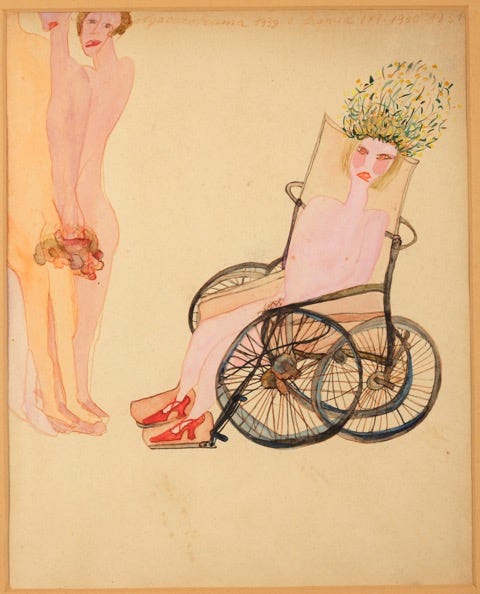

Rama was born in 1918. In 2003 when she was 85 and had twelve years to live, she was presented with the Golden Lion at the 50th Venice Biennale. Her being so lately revered is partly why Paul B. Preciado asserts her as a kind of phantom limb: a ghostly extremity of art history—severed and discarded, but panging nonetheless.

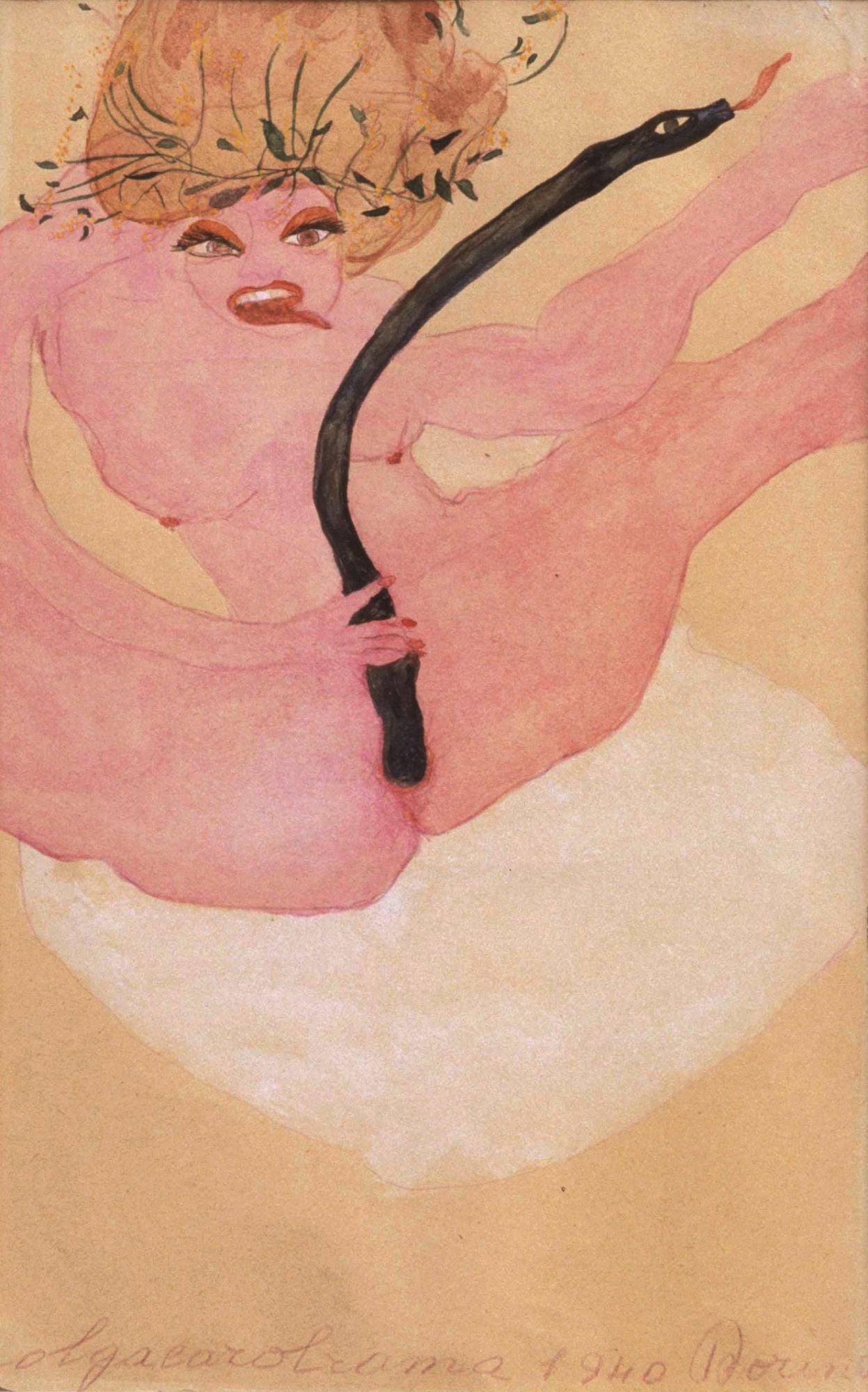

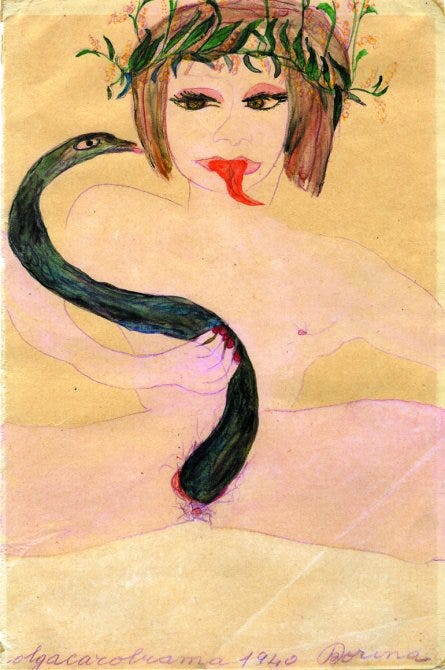

The figures in Rama’s early watercolours retain a taboo, charged power, but not because there is sex at play. Rather, it’s the brazen treatment of ‘outlandish’ bodies matter-of-factly at ease with their virility. We see women grasping the snakes that emerge from their vaginas—occasionally, they lock eyes and communicate carnal knowledge via their writhing tongues. Other women recline and kneel, their mouths parting toward the bouquet of phalluses being proffered at their shoulder.

Serpents, genitals and recurrent, salacious mouths—they come together with an anguished appeal that is distinctly gothic.

I can’t remember when, exactly, I learned that the watercolours depict patients of the asylum where Rama’s mother lived for many years. I know that as soon as I saw these images it struck me that neither subject nor artist makes any distinction between the figures’ lower and upper halves.

Rama’s brush falls upon their heads—the supposed repository of selfhood—in the same way it does that portion of us below the belt: the warm, divoted places where we are ebb and flow and smear and stain, where we let slip and blend with the world.

These are subjects with no interest in concealing the damp parts routinely hidden by those of us who are not—or not yet—‘mad’. In Lacanian terms, they’ve made none of the psychic sacrifices necessary to enter into the realm of the symbolic; they occupy a space where the body is foremost a series of orifices to be continually, zealously plundered.

In “Masturbazione”, painted in 1944, we see this equalising of upper and lower heavily rendered in oil. This work whose sole colour is a deep, gelatinous red shows a figure that was perhaps, at one time, a woman, and is now a pared back body sitting on a chair. Only the barest deviation of brushstrokes suggests limbs, a head. A few daubs signal the labia splaying around the wrist—the beginning of the actively invisibled fist. Another hand, subtler still, clasps the inner thigh.

When I saw this painting at IMMA in 2016, it was hanging alone in a passage between two rooms. It made me think of young Bone in Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina, specifically the sexual poetics the eight year old forges in light of her stepfather’s brutal sexual abuse.

‘I orgasmed on my hand to the dream of fire’, she tells us, while masturbating with her beloved trawling hook that rises, as if conjured, out of the river; ‘I took it back to my room, pried the chain off, and cleaned it and polished it. When it was shiny and smooth, I got in bed and put it between my legs, pulling it back and forth.’

The unapologetic vitality of the trawling hook was still on my mind when I heard Griselda Pollock refer to “Masturbazione” as a self-portrait.

Why had one conjured the other?

Probably, it had something to do with Pollock prisming Rama through Julia Kristeva’s assertion of the avant-garde as a poetics of dissidence: a direct challenge to the triumvirate of family, church and state. While it’s clear that Bone’s trawling hook corrupts the story her stepfather’s actions tell her about her own body, it took me longer to parse how “Masturbazione”—a work painted from inside a country partaking in a world war—pushed back against 19th century bourgeois society.

Now, I think its challenge is a simple one: a woman masturbating is sexual pleasure without the sex. What we see in “Masturbazione” is a woman awakening her organs to their own self-generated, self-sustaining pleasure, and doing so without yielding any reproductive capital. As such, she unhinges the conflation of social labour and sexual reproduction that upholds—amongst other things—military warfare.

All of which is to say: this red, slathered figure sitting on a wooden chair swallows nothing but her own skin, makes nothing but a snug loop by disappearing her hand into the hot pocket between her legs.

She is painted in red because she can only be red: what other colour signals the anticipatory heat of an orgasm? The labia parting like two warm, blood-rushed wings?

*

In Bluets, Maggie Nelson writes of a man with a

tattoo, a navy blue snake, which <she> liked to watch dance against the white of his wrist when the rest of his hand disappeared inside <her>.

While flicking through Bluets to look for this quote I stop at the words ‘tear’ and ‘sharp’ and ‘hurt’. Not ‘precious’, ‘orchids’ or ‘flowers’, which in fact precede it.

What words might precede “Masturbazione”, painted in 1944 and entirely in red in a dark room while a war wages and a river rushes by the window?

Maybe ‘dissolve’, ‘melt’ or ‘evanesce’, given that the painting seems to depict a subject creeping by flushed degrees toward pure sensation: those moments when the body is revealed as a simple vessel, rocked and governed by passing currents.

Or else—‘obliterate’, ‘efface’ or ‘liquidate’, given that this is work made in the knowledge that the closer we brush against all-consuming pleasure the more particularities we shed.

Dissipation. Generalisation.

This knowledge might be what Preciado means when he tells us Rama’s work neither expresses nor represents the body, but rather manages to make it an exclusively empirical object, ‘a biopolitical tapestry traversed by flows.’

*

In Volatile Bodies, Elizabeth Grosz writes that the clitorectomy is the only amputation that fails to conjure a phantom limb.

Can it be that the psychoanalytic understanding of female sexuality as castrated means that the surgical removal of an organ…already designated as lacking is not registered…

Which is another way of saying: we cannot perceive the lack of a lack.

How do we meet Rama now, if we couldn’t tell she was missing? Where does she rear up across the corpus of art history given that the phantom limb, when it returns, doesn’t always mimic its original self? The spectre of the missing part might be agonising, whereas the original bloomed in bliss.

When we look at Rama on the wall, do we see the work of an artist with a brush in her hand, or that of an eccentric in a dark room?

What excuses does the canon make for its lagging appraisal?

How are those excuses built into our encounter with the works in the here and now?

*

In The Argonauts, Nelson writes

I am interested in the fact that the clitoris, disguised as a discrete button, sweeps over the entire area like a manta ray.

It will never be true that Rama is more provocative or more intriguing for having been obscured.

It is true that the manta ray is a fish that swims with its capacious mouth wide open, and that it somersaults to stay in place while gorging on krill.

It is true, too, that the clitoris need emerge only in brief—need only show the very tip of what is a raucous, kinetic torrent of flesh—to boom like a rush of red thunder between the legs.

*

Supplementaries

This chapter by Preciado is rife with quintessential insights into Rama’s work and the wider context in which it was made. It’s also a wonderful introduction to Preciado’s work, if you’ve not had the pleasure of reading him until now:

Phantom Limb: Carol Rama & The History of Art

This talk by Griselda Pollock does a marvellous job of contextualising and analysing Rama in terms of fascism and feminism:

Writing Prompt

With any prompt I make regarding a work of art, my aim is to put meat on the bones of whatever critical discourse it might have generated up until that point: how does this work and its corresponding analysis unfold in the psyche, or indeed in the stomach or the heart? How can creative writing or the literary arts elucidate that unfolding?

If you give this one a whirl, I’d love to hear how you get on.

You open your fist and see a red line tracking the length of your palm. It ends in a swirl around the meaty base of your thumb: sits like a hazy sun above the horizon that is your wrist.

Write 100 words about its origin: where did this line come from? Is it a wound or a birthmark you somehow never noticed before? Is your impulse to keep it hidden, or flash your open hand at everyone you pass on the street? Will this mark be with you forever, or does it fade over the course of the day, leaving its thick smear on tablecloths and other pale strips of linen?

Have just got to this after having it saved since you published it. Such wonderful, incisive writing. And HOW have I never heard of/seen Rama before? Will be going on a deep-dive, starting with your extras here. Thank you xx