But, Reader, ‘a dream of’ is not right.

It was more of a dreaming into, or a dreaming toward.

This story begins on a March night as dark as night gets while you sleep. (3)

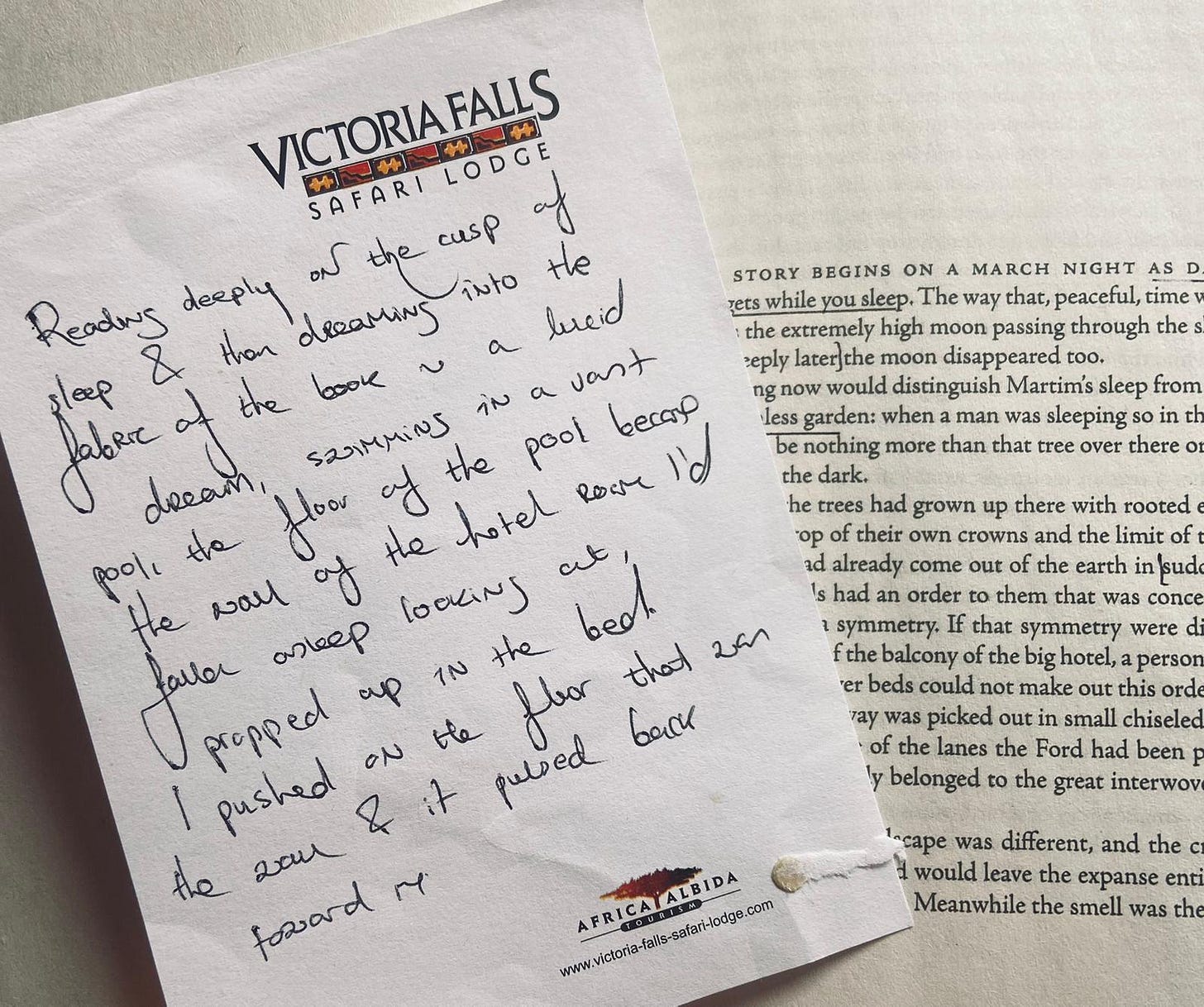

I am lying under a mosquito net, reading this muscular book. I am on the cusp of sleep, and when I do fall asleep I begin dreaming into the book’s very fabric, toward the novel’s atmosphere and tone. ‘Until much deeply later the moon disappeared too’, (3), ‘the voice of the cricket was the cricket’s own body,’ (4) ‘a vague alarm, whose irradiating center was the man himself’ (5)—all of this wefts around the dream which quickly reveals itself as lucid.

I am swimming in a vast pool. Far away from me, at its other end, people are sitting on steps and they are all partially submerged. I know I am dreaming because I am not a good enough swimmer to move like this in the wakeful world; easy and precise and smooth.

Without a backward glance, guided by a slick dexterity in his movements… (9)

Also—I do not need to draw breath. I simply swim and swim, my face pointing downward. The water on my back like a soft cloak.

When the novel opens, its protagonist, Martim, is not in a pool. He is jumping from a vacant building and moving through a vast landscape. He has just woken up, and I have just succumbed to sleep.

But, like Martim, I am verging upon a great truth.

Nobody had taught the man this connivance with whatever happens in the night, but a body knows. (9)

And then the floor of the pool becomes the wall of the hotel room. It is what I fell asleep looking at, propped up in the bed, this wall with its large mirror and the desk pushed up against it. I look at the bottom of the pool, the mirror, and see my sleeping self through the gauze of the mosquito net. I press on the floor of the pool that is the wall of the room and it pulses back towards me. It yields beneath my hand as though made solely for this instance of touch.

The pulsing is a kind of ecstasy, a promise of mutual access between two worlds.

After a few moments of this pulsing, this silken joy still being spun, I wake up.

It’s been twenty minutes or so, but I feel as though I am coming ‘round after a long, unfettered sleep.

In which stones would have opened their stone hearts and animals would have opened their secret of flesh… (253)

*

I’ve known for years that Lispector’s writing begets another place. Have known, too, that I cannot capture the meat and bones of going there.

But, still—this dream.

It felt not dissimilar to those moments at the end of the writing day when you look around your gilded, prosy cage and think: Where am I when I am not here?

*

Yes, I am awake; I can see the Zimbabwean bush through the balcony doors. The bush, through which impala are darting—soft graze of their haunches and their ducking heads. Tonight the elephant will come to the watering hole and squinting through the dark we’ll watch the whole herd slake its thirst.

The dream lingers on in the bright room. My husband is lifting our child from his crib and I know it was their soft, conversational sounds that roused me.

The heat of the body of the man and of the animals mingled in the same ammoniac warmth of the air. (104)

*

I had my first lucid dream when I was a child: I am running through the garden of the house I grew up in, I am turning back to look at the sky and the sky—it is full of a panther. Black and sleek and mid-stride. I have never seen anything this size. The panther: he is planetary. I cannot move or breathe because I am terrified. Not of the animal, but of his scale. He is all I see no matter how I move my head or eyes.

When I woke up I relayed the dream to my mother who told me a lucid dream is often signalled by an entity of an impossible size. She told me me, too, that a lucid dream is a sign you’ve left your body for a short time.

My mother, who will gift me “The Apple In The Dark” almost three decades later.

In the time between, I will start waking up in the night unable to move or breathe.

…as if that’s how you were supposed to behave when you’re afraid of the dark or initiated into spiritism and into the secret of a way of living. (76)

The first time, I was seventeen; flat on my back with a view of the digital clock on the nightstand beside me. It told me, in luminous red, that a minute had passed by. Which meant another minute was, now, also passing. How long did I have to make peace with my death?

Because I knew I was going to die. I’d never heard of sleep paralysis, this other hypnagogic state to which lucid dreaming is closely tied. I had simply woken up to my failed body: my lungs had fatally compressed and turned to empty pillowcases of crinkled silk while I slept.

I was terrified of death and there was a terror, too, in knowing I would leave the world without telling my parents or my sister goodbye. Another terror: one of them would have to find my cold corpse in the morning.

And then, at the point of true emptiness—a true absence of air—my body was returned to me and a breath staggered through my torso. It was an agony all its own, this breath. It ripped at me in all the places I was made of flesh. My every organ, a bolting horse. Surely my family would wake to the sound of my bones rattling in the bed.

…once again, as for a toothless god, the world would become something he could wander through, touchable. (252)

Over the years I’ve spoken with people similarly afflicted. The paralysis is always accompanied by terror, and almost always by a sense of violation.

A woman I used to see at galleries and dinners; when she was a teen, she spent the weekend with extended family and became certain her cousin was trying to rape her while she slept.

And for an instant…the woman too seemed to have claws in her bed, since something happens in the wetness of the night. (267)

A boy I went out with when I was young—a boy who once bit into the meat of my shoulder and told me I tasted like a salted pig—would wake up with someone sitting on his chest.

—Imagine a person who needed an act of violence, an act that made people reject him because he simply didn’t have the courage to reject himself. (210)

An uncle I haven’t seen for years: he told my mother he’d woken up in the dark and could not move. My mother said it happened to me all the time, that I’d gone to the doctor who said I had a certain hormone—one that stops you sleep-walking and sleep-talking—in excess. My mother told me that she could see it in my uncle’s face, how frightened he had been.

And finally free of the nightmare, she was astonished to find the night in the same place she’d left it. (269)

*

It doesn’t lessen the terror, to know what is happening to you. The thinking brain is no match for the loss of breath. It seems a certainty every time, that you will perish.

*

On the spectrum of sleep disorders, lucid dreaming is considered a sign that sleep paralysis has occurred.

The deep, deep peace I felt coming out of my Lispector-dream. The gift I had been given, in going there. The pulsing. I do not want to think it shrouded that wakeful terror.

*

Sleep paralysis is also called a false awakening.

But it was like a tiger who seems to laugh and then you see with relief that it’s just the shape of the mouth. (260)

*

If my glimpses are anything to go by, no sudden clarity will accompany my death.

Whenever I wake up stricken in the bed, the alleged truths I’ve built my life around simply shine more brightly.

—now behind all brightness was the darkness. And it was from there that the dark flame of his life would come. (117)

*

A part of me wishes I could leave my Lispector-dream alone, and not make it labour for me. Not sink my teeth into its retreating edges and put the pulsing to creative work. Not wonder what a sentence will do when it can’t tell if it’s written on the wall or on the floor. Will its edges smoulder with the threat of flame? Or will it convulse, one time, before slinking deeply into the inner ear’s dark coil? The same place that roars when filled with rushing water. How might prose be contoured by an unlikely pulse that contains the motions of this singular world? How many times must you bear down on a clause, before ripples begin to form?

I do. I wish I could leave it be. And yet—

WRITING PROMPT

You are in a room you have no memory of entering. You have no desire to leave and, besides, there is no door. You are warm and wet because you never left the amniotic sac. No: it is because you are swimming. You let yourself sink because there is more air the deeper you go. And you want to know what it feels like, the silken film that is the floor. What happens to your hands when you land, palm-flat? How long does it take for this contact to traverse your torso and thighs, your buoyant ankles?